Joe Fulks, the Jump Shot Innovator One Man Murdered and the Rest Forgot

The jump shot has a handful of fathers, most of whom have been forgotten by all but the hardest-core of hardwood fans. Among these innovators was Joe Fulks, whose life story puts him in a singular category: he’s the only Hall of Fame player — in Springfield, Canton, or Cooperstown — to have been murdered.

In the beginning, there were two peach buckets, nailed to the lower rung of a balcony on opposite ends of a gym. Dr. James Naismith laid out the rules for basketball in 1891, including №8, which defined the relationship between ball and basket.

Goal shall be made when the ball is thrown or batted from the ground into the basket and stays there, providing those defending the goal do not touch or disturb the goal. If the ball rests on the edge and the opponents move the basket, it shall count as a goal.

It’s amazing how Naismith’s original vision has remained steadfast, at least in what remains the game’s heartbeat: 125 years later, the ball is still more or less “thrown” into the basket.

Of course, other aspects of the game have evolved in that time. It took Naismith et al a couple years to figure out that cutting holes in the bottom of the basket would speed things up. There is no official genesis for the jump shot, however — no definitive moment of clarity when men decided to abandon the two-handed, stationary, feet-nailed-to-the-floor shots that defined basketball’s early years.

In his book Cages to Jump Shots, basketball writer Robert W. Peterson says that there are stories of a jump shooter as far back as 1901–02, when, as recalled by _Trenton Times_ sports editor Marvin A. Riley, a player named Jack “Snake” Deal, on the American League’s Camden squad, “never set for a shot — he took them on the jump — and landed them too.” Apocryphal or not, Peterson notes that nobody slithered in Snake’s footsteps: the jump shot “which revolutionized basketball … did not appear regularly in the pro game come until the late 1940s, when Jumping Joe Fulks began setting scoring records.”

Fellow hoops historian John Christgau considers Fulks part of an exclusive club of eight men who lifted the game off the hardwood, which he chronicles his book The Origins of the Jump Shot. In his estimation, the salient point isn’t who exactly shot what when but rather the “story on the origins of creativity itself.” (Another pioneering shooter, Kenny Sailors, who led the University of Wyoming to its only national title in 1943, passed away last month, at the age of 95.)

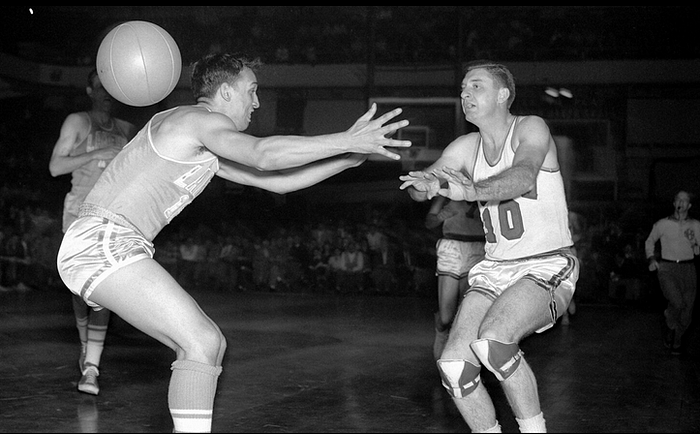

Christgau, 81, first encountered Fulks as a high schooler in Minnesota, when his Philadelphia Warriors would come to town to play George Mikan’s Laker squads. Fulks, a small forward known for spinning in the air, changed the way the young prep star saw the game. “Our high school coach preached this awful two-handed set shot, and maybe a one-handed runner, all in service of a slow, deliberate pace. Quick decisions weren’t the norm in those days,” Christgau says. “Fulks was a revelation. In my mind, he completely distinguished himself from everyone else in the league. He had a high release, just a dynamic ingenious jumper. I knew I had to learn that shot. Back then, when you went up, nobody would be in your line of sight, so in the air, there was an almost serene sense of tranquility.”

Christgau would go on to play power forward at San Francisco State, a school he selected because it had one of the best writing programs in the country. Origins of the Jump Shot was his ninth nonfiction book; his chapter “Joe and His Magic Shot” is the primary biography of Fulks.

“I bet if you asked a thousand basketball fans of all ages, there might be five who had ever heard of Fulks,” says Christgau. “I’m fascinated by stories of promise unrealized. In a suit and tie, straight and sober, he could have been a model, a corporate president, anything he wanted. He’s a forgotten figure, sadly.”

Joseph Franklin Fulks was born in 1921 on a farm outside Birmingham, a small town between the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers in Western Kentucky. It had once been a center of iron mining, but the ore deposits were barren by the turn of the century; by the time Joe came along, the town was in desperate straits. The main industry for many poor backwoods folk and sharecroppers was supplying what bootleggers considered “the best moonshine in the world” to Al Capone’s Chicago empire.

The Fulks, like most families in the area, were penniless. According to Christgau, Joe’s school only had two basketballs; practicing at home meant pretending to dribble a sock stuffed with rags, toilet paper, or sawdust. His father, Leonard, drank, and the family was always on the margins. Joe was a shy, sullen kid, and a nearly fatal black widow bite caused him to withdraw even more. Shooting baskets alone on a ramshackle hoop became his refuge from everyday hardship. It’s a familiar basketball story right through to today.

The Fulks moved into the town of Birmingham, and Joe’s reputation started to grow. In high school, his “magic shot” — where he would spin, jump, and fire with either hand — earned him a spot on the all-state team. Prior to his senior season, in 1938, the Fulks moved to nearby Kuttawa, a basketball hotbed along the Cumberland River. Leonard had gotten a job as a guard at the Kentucky State Prison in nearby Eddyville — which was fortunate for the Fulks, because Birmingham would soon cease to exist. In a few years, the Tennessee Valley Authority would finish building the Kentucky Dam and, in a Great Depression dirge come to life, Birmingham would be submerged, gone forever (though rumor has it that you can still see foundations and roads when the water level is low).

Fulks had a successful senior campaign, although an ankle injury kept him out of the Kentucky state high school tournament and Kuttawa lost in the first round. He attended Murray State, where he averaged 13 points a game over his college basketball career, and received All-American honors in 1943. After his second season on the Thoroughbreds (Murray State hoops switched to the Racers in 1961), Fulks was drafted into the Marine Corps, and saw action in the South Pacific during World War II.

During the war, Fulks continued playing ball for the Fleet Marine Force at Pearl Harbor. Eddie Gottlieb, a coach and general manager in the brand new Basketball Association of America, got wind of the skinny 6'5 shooter with the deft touch. He signed Fulks to the Philadelphia Warriors in 1946, the BAA’s inaugural year, for $8,000.

Jumpin’ Joe dominated the league from his first tip-off, scoring a game-high 25 points in a 81–75 win over the Pittsburgh Ironmen. Peterson described Fulks’ instantaneous impact on the game in Cages to Jump Shots:

There may have been other jumpers before him, but Joe Fulks was the first to exploit the shot to its fullest. Within a decade it would be the primary offensive weapon in the National Basketball Association… His turnaround jumpers from the pivot captivated crowds. His high-arching shots seemed to float toward the basket. Knowing a good thing when he saw it, Eddie Gottlieb had the Warriors feed Fulks, who soon became the darling of the young league.

At the end of the 1946–47 season, Fulks led the BAA in scoring with 23.2 points a game; the league (and the Warriors) averaged 68; the nearest runner-up to Fulks was Bob Feerick of the Washington Capitols, who only dropped 16.8 a night. In the playoffs, the Warriors defeated the Chicago Stags 4–1 to win the chip.

For Ernie Beck, a Philadelphia native who would eventually join Fulks on the Warriors, it wasn’t just the winning that mattered; it was the exciting, unique way Fulks was mastering the game. “When I was playing in high school, we could go watch the Warriors for free. I thought Fulks was the best Philly had ever seen, even though we laughed that he was such a ballhog,” says Beck, now 85 and a recent enshrinee in Philadelphia’s hall of fame. “He had a hook from the right and left sides, good spring in his legs, and an over-the-head jump shot, if you can believe it. Joe was just a great ballplayer.”

Fulks was a sensation in the BAA, enabling the fledgling league to find its bearings. For his first scoring title, the Warriors rewarded Fulks with a Buick, which he drove back to Kuttawa for a summer spent on a houseboat with a group of boozehounds. He returned the next season to again lead all scorers with 22.1 PPG. He also took the Warriors back to the finals, where they lost to the Baltimore Bullets 4–2. In 1948–49, the BAA’s last season before merging with the rival National Basketball League to form the NBA, the struggling Warriors finished with a 28–32 record, but Fulks kept filling it up at 26 PPG, second only to George Mikan’s 28.3. It would be Fulks’s last stellar year, and was capped off by an epic single-game scoring barrage.

A blizzard hit Philadelphia on the night of February 10, 1949, both outside and inside the arena. Mikan had set the single-game scoring record 11 days earlier, with 48; Fulks eclipsed that mark in the third quarter against the Indianapolis Jets. Coach Gottlieb would later recall that, during a timeout and with a couple minutes remaining, he encouraged ol’ Joe to basket-hang so he could hit a seemingly impossible 60. Fulks shook his head and said, “I don’t want points that way. I’ll earn them.” He wound up shredding the Jets, going 27-for-56 from the field and 9-for-14 from the line for a total of 63 points. The record would stand for a decade, until Elgin Baylor dropped 64 in 1959. (It’s worth noting that Baylor’s binge came after the NBA instituted the 24-second shot clock.)

Fulks had three more productive years with the Warriors, but he never reached 20 PPG again. By his final season, in 1953–54, he was a shell of his former self, according to teammate Walter “Buddy” Davis. “Joe had more talent than he had any idea what to do with it, but by the time I got there, he was way over the hill, just hanging on due to past glory,” says Davis, 85, who now lives in Groves, Texas, fishing as often as he can with his wife of 65 years.

“At training camp that year, Joe didn’t participate in hardly any drills or scrimmages, and after the season started, he didn’t play much. He’d make a ceremonial appearance in every ball game, usually take a couple of shots, mostly from long range, and then come out of the game. But even though Joe was well past his playing prime, his shooting was adapted by 90 percent of the players in the NBA.”

It was no secret that, like his old man, Joe Fulks was a heavy drinker. In The Origins of the Jump Shot, Christgau says Fulks told Philadelphia sportswriters that liquor had always been in his life, going back to the Birmingham bootleggers, and that in Kuttawa soda fountain Cokes came fortified with whiskey. Fulks, a self-proclaimed hillbilly, never took to city life, and filled a lot of his spare time in Philadelphia getting loaded.

“Joe was country, for sure,” says Beck, who never left Philadelphia. “I hate to speak ill of the dead, but he liked his beer. Eddie [Gottlieb] would check on him to make sure he wasn’t out before the game, so Joe used to hide a case of beer in the closet. He would have a few before playing, I never understood how he could do that. After he retired he came to one of our games in St. Louis… Well, it’s a terrible thing because he was a nice decent man, a really great guy.”

Fulks’ drinking was clearly a problem, but it was also a different era. The American Medical Association didn’t define alcoholism as a disease until 1956. Alcoholics Anonymous existed, but on a much smaller scale. A drinker’s always going to drink until they stop, but in post-World War II America, it wouldn’t have occurred to the Warriors to dry out Fulks in a sanitarium. Back then, it was seen as a character flaw. Jumpin’ Joe was on his own.

After he left basketball, Fulks moved back home and his life became a Steve Earle song. He washed out of a couple of jobs, but eventually both he and Leonard sobered up. Joe even did a bit of scouting for the Warriors.

Fulks had one last moment in the basketball sun in 1971, when he was selected to the NBA’s silver anniversary team along with Bill Russell, Bob Cousy, and George Mikan, his old anything-you-can-score-I-can-score-better nemesis. The honor, however, would be his undoing. He started drinking with his old friends and teammates at the San Diego celebration and never stopped. Fulks was as popular as ever, but he wouldn’t live to attend his official enshrinement in Springfield seven years later.

Once again, Fulks again ended up following in his daddy’s footsteps. By 1976, he was working as an athletic director in Eddyville at the Kentucky State Penitentiary, the massive and probably haunted “Castle on the Cumberland” that today houses the Bluegrass State’s most notorious criminals. After work on March 20, Fulks went to visit his girlfriend Roberta Bannister at her home in Beckett’s Trailer Court. Her 22-year-old son Greg, who adored his father and thus didn’t care for Joe, was there with his his wife, Sharon. The night started peacefully enough — Greg even helped Joe fix his car. By 10pm, however, both men were in their cups, arguing around a small kitchen table while drowning cheap Tvarscki vodka.

The night got later, louder, and drunker. The two started arguing over a .38 pistol, which belonged to Sharon, and which Joe had carried to the back bedroom. Eventually, Greg retrieved a double-barreled shotgun from the trunk of his car. He stormed back into the bedroom, where a sozzled Fulks sat on the bed alone, and demanded that he leave. Moments later, Joe Fulks was dead, his blood pooled on the floor. The point-blank blast severed the carotid artery in his neck. He was 54 years old.

At 5:30am, Greg Bannister was taken to the hospital by the county sheriff and sedated — he still had a blood-alcohol level of .2, twice Kentucky’s legal limit. He was booked and bail was set at $50,000. A grand jury found Bannister guilty of “reckless homicide,” and he was sentenced to four and a half years. He was released on parole in less than two. Bannister’s probation appeal included a vow of sobriety, but he would be arrested and sentenced again and again for alcohol-related offenses.

It would stand to reason that the violent murder of a professional basketball superstar would be quite a story, but Fulks’ death barely made a ripple. Perhaps he’d been out of the game too long, or played before anyone truly paid attention; maybe two blotto hayseeds messing around with firearms in a trailer park didn’t qualify as news. The Bowling Green Daily News ran a brief AP story on page seven. No Warriors attended the funeral. Fulks was buried in a small cemetery, alongside the graves relocated from the lost city of Birmingham.

His murder was remembered by a few Kentucky basketball junkies, but the details weren’t really known publicly until Christgau researched and wrote The Origins of the Jump Shot in 1999. Even today, Fulks’ death remains more or less anonymous. All these years later, Beck thought he perished in a bar fight or maybe a car accident. Davis was told he was walking home from a bar, tripped into a ditch, and drowned. Neither man knew their former teammate had been murdered. Both were sorry to hear it.

“After road games, we would go to a local bar and have a couple of beers and Joe was always with us,” says Davis. “He was an all-around Good Time Charlie, but I didn’t know anyone that didn’t like Joe Fulks.”

Fulks was posthumously inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 1978.

The Golden State Warriors opened their season this year with a ring and banner ceremony on October 27th. They invited a representative from each of the three previous championship teams to take the floor for the pre-game festivities. The 1946–47 Philadelphia Warriors were represented by Howie Dallmar, Jr., whose father, a starting forward for Philly, passed away in 1991, at the age of 69. Only one member from the title-winning team is still alive: 92-year-young Jerry Rullo. Unlike Joe, the rest of the Warriors lived long lives, lasting from their 70s into their 90s.

Walt Davis stood in the spotlight for the ’56 Philadelphia Warriors. “It was indescribable. The Warriors were kind enough to send my son with me to help me out,” he said.

Davis went in place of Beck, who no longer likes to fly — and who already regrets the decision. “I didn’t think my grandson could go. My family is so damn mad at me,” he said. “Wish I’d gone. Just one of those things.”

The talk of the night was, of course, the 2015 Golden State Warriors and the man with a few magic shots of his own, Steph Curry. John Christgau says that, due to the range and off-the-dribble factors, Curry is the best shooter of all time, bar none.

Davis was giddy to have seen him in person. “Stephen Curry has the fastest trigger I’ve ever seen,” he said. “All he needs is one little look and he fires. He had 25 points in the first quarter that night.”

While praising Steph, Beck, Christgau, and Davis all mentioned Curry’s forefather, the man who brought the jump shot into its own. Through Warrior lineage and steely marksmanship, Curry is carrying on the tradition that Fulks elevated seven decades ago. On its 125th birthday, the game of basketball is better thanks to both of them.